Taíno genocide

| Taíno genocide | |

|---|---|

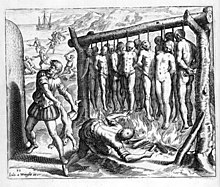

A 16th-century illustration by Flemish Protestant Theodor de Bry for Bartolomé de las Casas' Brevisima relación de la destrucción de las Indias, depicting Spanish torture of Indigenous peoples during the conquest of Hispaniola. | |

| Location | West Indies |

| Date | 1493 - 1550 |

| Target | Taíno |

Attack type | Genocide, slavery |

| Perpetrators | Spanish Empire |

| Motive | Colonialism Spanish imperialism |

| Part of a series on |

| Genocide of Indigenous peoples |

|---|

| Issues |

The Taíno genocide was committed against the Taíno indigenous people by the Spanish during their colonization of the Americas which they started in the Caribbean during the 16th century. It is estimated that before the Spanish Empire arrived on the island of Quisqueya[1] (which Christopher Columbus baptized as Hispaniola), the Taíno community had between 100,000 and 1,000,000 inhabitants[2] who were subjected to slavery and other treatment violent after the last Taíno chief was deposed in 1504. By 1514, the population had been reduced to just 32,000 Taíno,[2] by 1565 the number was 200, and by 1802 they were declared extinct However, National Geographic carried out a report in 2019, revealing that descendants did exist and that their disappearance from records was part of a fictional story created by the Spanish Empire with the intention of erasing them of history.[3]

The Taíno people were the descendants of the Arawak people who arrived in America approximately 4000 years before the conquest, [3] and they lived in the Bahamas, the Greater Antilles and the Lesser Antilles.[4] Christopher Columbus was looking for gold, however, when he did not find it, he focused on the slave business. Upon arriving at the island, a confrontation occurred between the colonizers crew of Santa María and the Taíno after the first sexually abused of the native women.[1] In 1503 most of the caciques were captured and burned alive.[1] Fray Bartolomé de las Casas wrote that in that massacre the Spanish also attacked the other inhabitants, cutting off the children's legs as they ran.[1]

For several months after that event, Nicolás de Ovando continued a campaign of persecution against the Taíno until their numbers became very small, [1] according to historian Samuel M. Wilson in his book Hispaniola. Caribbean Chiefdoms in the Age of Columbus. The Taíno suffered physical abuse in the gold mines and sugar cane fields, as well as religious persecution during the Spanish Inquisition, along with the exposure to diseases who arrived with the colonizers.[3] Others were captured and taken to Spain to be traded as slaves, which resulted in numerous deaths due to poor human conditions during the journey.[5]

In thirty years, between 80% and 90% of the Taíno population died.[6][7] Because of the increased number of people (Spanish) on the island, there was a higher demand for food. Taíno cultivation was converted to Spanish methods. In hopes of frustrating the Spanish, some Taínos refused to plant or harvest their crops. The supply of food became so low in 1495 and 1496 that some 50,000 died from famine.[8] Historians have determined that the massive decline was due more to infectious disease outbreaks than any warfare or direct attacks.[9][10] By 1507, their numbers had shrunk to 60,000. Scholars believe that epidemic disease (smallpox, influenza, measles, and typhus) was an overwhelming cause of the population decline of the Indigenous people,[11] and also attributed a "large number of Taíno deaths...to the continuing bondage systems" that existed.[12][13] Academics, such as historian Andrés Reséndez of the University of California, Davis, assert that disease alone does not explain the destruction of Indigenous populations of Hispaniola. While the populations of Europe rebounded following the devastating population decline associated with the Black Death, there was no such rebound for the Indigenous populations of the Caribbean. He concludes that, even though the Spanish were aware of deadly diseases such as smallpox, there is no mention of them in the New World until 1519, meaning perhaps they did not spread as fast as initially believed, and that, unlike Europeans, the Indigenous populations were subjected to enslavement, exploitation, and forced labor in gold and silver mines on an enormous scale.[14] Reséndez says that "slavery has emerged as a major killer" of the Indigenous people of the Caribbean.[15] Anthropologist Jason Hickel estimates that the lethal forced labor in these mines killed a third of the Indigenous people there every six months.[16]

Subsequently, in the United States, Yale University classified the atrocities which the Spanish Empire committed against the Taíno as a «genocide» and it also included the Taíno genocide in its Genocide Studies Program.[2]

See also[edit]

- Taíno

- Colonialism and genocide

- Genocide of indigenous peoples

- Genocides in history

- Indigenous response to colonialism

- List of ethnic cleansing campaigns

- List of genocides

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e Carolina Pichardo (October 12, 2022). "Anacaona, the Aboriginal chieftain who defied Christopher Columbus and was sentenced to a tragic death". BBC News Mundo.

- ^ a b c "Hispaniola - Genocide Studies Program". Yale University.

- ^ a b c "Meet the survivors of a "genocide on paper"". National Geographic. October 15, 2019.

- ^ Luis Méndez (October 12, 2022). "The Taínos: the indigenous people who became extinct in the Caribbean after the Spanish conquest". The News.

- ^ "How the Conquest of America claimed the lives of more than 50 million people". CNN in Spanish. October 11, 2022.

- ^ "La tragédie des Taïnos", in L'Histoire n°322, July–August 2007, p. 16.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Diaz Solerwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Anghiera Pietro Martire D' (July 2009). De Orbe Novo, the Eight Decades of Peter Martyr D'Anghera. BiblioBazaar. p. 108. ISBN 9781113147608. Retrieved 21 July 2010.

- ^ Anghiera Pietro Martire D' (July 2009). De Orbe Novo, the Eight Decades of Peter Martyr D'Anghera. BiblioBazaar. p. 160. ISBN 9781113147608. Retrieved 21 July 2010.

- ^ Arthur C. Aufderheide; Conrado Rodríguez-Martín; Odin Langsjoen (1998). The Cambridge encyclopedia of human paleopathology. Cambridge University Press. pp. 204. ISBN 978-0-521-55203-5. Archived from the original on 2016-02-02. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- ^ Watts, Sheldon (2003). Disease and medicine in world history. Routledge. pp. 86, 91. ISBN 978-0-415-27816-4. Archived from the original on 2016-02-02. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- ^ Schimmer, Russell. "Puerto Rico". Genocide Studies Program. Yale University. Archived from the original on 2011-09-08. Retrieved 2011-12-04.

- ^ Raudzens, George (2003). Technology, Disease, and Colonial Conquests, Sixteenth to Eighteenth Centuries. Brill. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-391-04206-3. Archived from the original on 2016-02-02. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- ^ Treuer, David (May 13, 2016). "The new book 'The Other Slavery' will make you rethink American history". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 23, 2019. Retrieved June 22, 2019.

- ^ Reséndez, Andrés (2016). The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 17. ISBN 978-0547640983. Archived from the original on 2019-10-14. Retrieved 2019-06-21.

- ^ Hickel, Jason (2018). The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and its Solutions. Windmill Books. p. 70. ISBN 978-1786090034.